Editor’s note: This essay originally appeared in Ansible 8, edited by Jorge Villacorta, Andrés Hare and Alfredo Bernal in Lima, Peru. An expanded version, in French, was published as “Du Musée au Panthéon”, in Passés, Futurs, 6 (2019), in the special issue “L’humanité en vitrine”, edited by Silvia Sebastiani.

In 1878, the Argentine ex-president Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (1811-1888), the famous author of Facundo (or, as it were, Civilization and Barbarism: Physical Aspects of the Argentine Republic, and the Ideas, Customs and Characters it Engenders, Santiago de Chile, 1845) arrived on the first floor of Buenos Aires’ old Teatro Colon. At a slow but sustained pace, he climbed seventy well-counted stairs. In a fortunate delirium, perhaps caused by his age, he thought he was in Dante’s portal to hell, at least as presented in the illustrations of Gustave Dore.

He had, in reality, passed through the entrance of the Anthropological and Archaeological Museum of the Province, inaugurated in August 1878 on the theater’s upper floors. The year before, the government minister, Vicente Quesada, had accepted the conditions stipulated in the donation of Francisco Pascasio Moreno’s (1852-1919) collection: “more than fifteen thousand Argentine archaeological and anthropological specimens or those from the Natural Sciences that relate to their study” […] gathered “personally during my trips and with their authenticity guaranteed.” (AHPBA) In that act, Moreno presented these objects as being his own work, and, thus, these diverse objects were subsumed under his authority.

L,R: Crossing of Lake Cocito by Gustave Doré (L'Enfer de Dante Alighieri, avec les dessins de Gustave Doré. Traduction française de Pier Angelo Fiorentino, accompagnée du texte italien, Paris, Hachette, 1862)

“The human comedy according to young Moreno”, said Sarmiento probably thinking of the image of the crossing of Lake Cocito’s freezing waters, in the ninth circle of hell, where the eyes of the traitors to the family look at the poets from below, nearly peeking out from the waters. In Moreno’s museum, however, the empty eyes and the skulls, without skin or hair, of some tens of Indians, and some white people, looked at him from above, lined up on shelves. Sarmiento, nevertheless, recognized the difference between the hellish images evoked by poetry and the scientific exhibition of the bones of actual people. “With these reflections, the modern poets who do not lineate their words in verse, but rather natural objects in series that give cause, and penetrate the anthropological ossuary. […] From all the angles of the vast pantheon, one looks without seeing, at a thousand human crania, with their empty holes, black, shadowed and always fixed.” (Sarmiento, 1951: 135-6) Sarmiento recognized the importance of the series in the science of the 19th century and the possibility of extracting from generalized quantity, rather than from individuals, the skeleton key to their life of human groups.

The bodies – or, put better, the skeletons’ bones – had been other places, some in Patagonia, others crumbling in drawers, one or another having also been exhibited in public. Still, together or separate, the bones of the anthropological collections appeared to conjure those of old whose woes were said to have pursued Seneca, and, later, Francisco de Quevedo: for the dead man, water undoes him; the air wipes him away; the fire dries him; the worms eat him; animals tear him apart; the birds pick at him; fish swallow him. Not for naught did those in antiquity say the loss of burial is easy: it was invented to rid ourselves of stinking corpses. The nineteenth-century museum thought up a place to look at them without the smell, and with the promise of conserving them for eternity. Of course, as the Museo de la Plata’s collections show, eternity did not extend to arriving at the final judgement. The present work, referring to episodes from the history of the anthropological collections of the Museo de la Plata, intends to show the constitutive disorder of its formation to discuss, on one hand, how the debates of the time naturalized as history that which solely existed in the hagiographies and celebrations of the life of its founder; on the other, how, in the questioning of the exhibition and conservation of skulls and skeletons, their more diverse aspects are conflated. To this end, based on interviews and archival investigation and on what has been produced in the field, I will open the case of the Mapuche Pantheon of the city of Trenque Lauquen (Province of Buenos Aires) and the projects at stake in the year 1989.

Moreno’s Collections and the Museo De La Plata

Until 1878, when Francisco Moreno’s collections were transferred to the city center, they were stored in discrete places on his family’s property, six blocks from the current neighborhood of Parque Patricios, the southwest limit of the city of Buenos Aires (Farro, Podgorny and Lopes). There, his maternal grandfather’s residence was, during Moreno’s adolescence, the source of various paleontological pieces, shared between Francisco and his brothers, the latter of whom later left them for the world of finance.

The donation to the Province did not imply the unconditional gift of these objects. On the contrary, in doing so by act of government, Moreno linked them to his own destiny: his collection could not “be divided in fractions nor pass to any other establishment than that to which they would be provided to at the beginning, nor could anything ever be combined with any other [collection]”. In contrast to the American magnates, founders of truly private establishments, Moreno conceived of the museum as a business subsidized by the State — in this case, the provincial state. Thus, in the Buenos Aires budget of 1883, the Anthropological Museum carried the following costs: “Entry 40 of the Department of Government, Item 7, Anthropological Museum”: one director, 5000 per month; an assistant 1000 and a porter 500, total 6500 per month or 78,000 annually in addition to the general costs of the Department of Government, Entry 6, Item 15”; rent on the house, 24,000 per year; Item 16, office costs: 6000 per year, for a total of 108,000 pesos annually. By way of comparison, the Public Museum, the future National Museum, was given 193,900 pesos. The minister of government, on the other hand, received 17,500 pesos monthly, which is to say an annual total of 210,000 pesos.

On November 13, 1877 the government ministry appointed Moreno the director of the Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology, stipulating that each year he would need to compile a report in which he would note increases in the collections and the results of his exploratory trips across the Republic. Likewise, they needed to gather and conserve an archive of the communications specifically referring to the same establishment and to proceed to drafting its catalog, before undergoing the scientific classification of its objects. They also stipulated, for the moment, that the collections be housed in the building belonging to the family, with the obligation of the director being their care, conservation and growth. These consisted of objects and skulls of distinct provenance. Among them:

“252 human skulls taken from ancient indigenous cemeteries of the Rio Negro Valley. They represent various sorts of current and extinct races from Patagonia. -20 skulls from living Indians from Patagonia (Tehuelches and Pampas). A Huarpe skull (Calingasta). -2 skulls from the ancient Indians of the Calchaqui Valley (Granadillas, Province of Catamarca). An ancient indigenous skull from the province of Santiago del Estero (in the middle of Rio Dulce). -An incomplete indigenous skull, extracted from the same place. -A Toba Indian (Gran Chaco) skull. -An Indian skull of the Peruvian race. -A Malay skull. -Two skulls with yet unknown provenance. These skulls have been sent by Professor Broca, though the letter with the details has been lost. -Six European skulls. -One child’s skull demonstrating dental changes. -Five skulls from human fetuses. -Six molds of skulls (in plaster) from Chiriquies, Chimoock, Aimaraes, Quichuas, sent by Quatrefages.-Three molds sent by Professor van Benden, from Liege, representing the skull and the cerebral cavity of a Neanderthal man and the skull from Engis.-15 molds of skulls sent by Professor Paul Broca representing an Eskimo, 2 Mongols, one habitant of Singapore, a Mande, two habitants of the Baye cave, from the New Stone Age. Three from Orrouy. One from Quiberon, two from the Roknia dolmen, the skull from Engis, and one trepanned skull from the cave or grotto at Baye. Six busts in painted plaster representing a black Charrúa, one mestizo Charrúa, a Chimook, a woman, one Ottowas, man and two Chippway, man and woman, sent by Mr. Quatrefages. One Moluche Indian, mummified, recovered near the Rio Negro. One mummy exhumed in Punta Walicho (Argentine Lake) Patagonia (Fuegian Race). Seven more or less complete skeletons of Tehuelche and Araucanian Indians, a European skeleton. 200 long bones, various pelvises, sacral bones, scapulae and other loose bones from skeletons extracted from the ancient cemeteries of Rio Negro. A complete collection of 33 examples from the New Stone Age, from Denmark, representing daggers, knives, axes, hammers, spearheads and arrowheads sent from the Museum of Copenhagen. A collection composed of 26 stone instruments used by the Quaternary man of Belgium and France, sent by Professor E. van Benden from Liege. A collection composed of more than 400 objects, such as bows, arrows, lances, maces, axes, domestic tools, adornments, etcetera, of the existent Indians of Gran Chaco, Pampas, Patagonia, Bolivia, and Brazil. A collection of stone arrowheads, bone and adornments made of mollusks and bird bones from the Indians of Tierra del Fuego. A collection of objects belonging to the ancient habitants of the Province of Buenos Aires, representing stone weapons and pottery. 5000 (more or less) knapped flints including arrowheads, darts, scrapers, axes, etc from the ancient habitants of Patagonia, collected in the Valley of the Rio Negro, Chubut, Puerto Deseado, Rio Santa Cruz, the straits of Magellan, etc.-A collection of 350 objects recovered from the Calchaquies Valleys, and the Province of Santiago de Estero, representing stone and copper weapons; further, disk covers in copper, stone mortars, animal and human figures in rock, flagon cups and plates in baked earth, and funerary urns. -A collection of more than a thousand fragments of painted pottery, recovered on the shores of the Rio Dulce, Santiago del Estero province. Four Ancient Peruvian vases. -110 objects belonging to the ancient Patagones, representing various classes of mortars, discs for crushing roots and fruits, instruments for preparing leather boleadoras, scrapers, etc, recovered in the Rio Negro, Chubut and Santa Cruz valleys. -Various examples of ancient pottery from the Charrúas, Minuanes, Corondas. -15 ancient objects of the habitants of the province of Salta.*

Those collections, visited by Sarmiento in 1878, would, a few years later, be “recast in another museum”, according to its director’s plan, which ran contrary to the museum’s own charter. Moreno, in 1880, found refuge in Paris after having deserted one of his trips to Patagonia. There he began to whip up the idea of a grand national museum in the city of Buenos Aires, by now the capital of the nation. In those years, the future location of the provincial administration was unknown, as was the way in which they would split up the existing institutions including, among others, the public and anthropological museums, the library, and the archive. Moreno pushed for a project to create a “National Museum of Archaeology, Anthropology and Natural History”, which, while passing in the legislative chambers, did not pass into reality. (Podgorny and Lopes, 2002; Podgorny, 2009)

Against this, in 1884, the old Public Museum was nationalized destroying the plans for the monumental building. Moreno, meanwhile, had been negotiating with the authorities established in the nonexistent city of La Plata, the new provincial capital, which, in 1882, began to be constructed 60km to the south of Buenos Aires. The new Museo General (and provincial) of La Plata got its building, but it lost its specific character in order to incorporate everything from geology to contemporary industrial production. Repeatedly inaugurated in order to please the government in power, it had to redefine its goals many more times in order to survive the changes in political context and the recurrent administrative crises in the country. In 1885, during one of its openings, Sarmiento traveled to La Plata, this time to celebrate the “scientific exhibition” of that Pampas which was in the process of extinction (Podgorny, 1998).

The museo general de la plata’s monumental building

The monumental, specially constructed, building was expensive and never finished being filled. The letters from the director to traveling naturalists abound in instructions to this effect: gather giant pieces, collect hundreds of skulls to impress the politicians, and, in that manner, raise the funds to be able to proceed forward. In that context, the most atrocious and diverse aberrations occurred that today fill pages, documentaries and novels which pertain to every interest: indigenous prisoners who were made to live and die in the museum; conflicts with the municipal authorities; confrontations between the director and the employees who disobeyed him, sold collections and realized their own projects thanks to permission received from the governorship to hunt down and collect. The skulls and skeletons that were deposited in the second half of 1880 give an account of this, but also show the administrative disorder that ruled in the museum and the incapacity to register what was entered into it—dead or alive—and what left to be sold elsewhere. It was in this respect that the local press accused Moreno and the governor of acting outside the municipal provisions in not officially registering the deaths of the indigenous people, and upon which the employees likewise took advantage of the regime of infraction. Some turned to alcohol as the object of their observations; more than one preparer copied the practice of the Cacique women who went to the city to sell woven fabrics (though in the corridors of the institution) and, in that fashion, made themselves a few extra pesos to alleviate their misery. The fabrics, and their embroidery, ended up who knows where.

In an indication of the state of these confrontations, Florentino Ameghino (1853-1911), ex-subdirector of the museum, sent a letter in June 1889 to a fossils and antiquities dealer from Northwestern Argentina, authorizing him to disseminate it. The addressee was looking to use it as propaganda: he published it in La Nación, which censored the parts where the Museo de la Plata was referred to, and in full in the Figaro on June 28th 1889. There he described the state of things, which, true or not, reveal a dynamic stained by the pressure to justify the existence of said institution:

“I don’t advise you to choose the Museo de La Plata. That establishment offers not even the most minimal guarantee of seriousness, as it is in the hands of a megalomaniac who dreams and raves of grandeur, which, with his continuous chatter of hollow, meaningless, stereotypical phrases, is making our country out to be ridiculous abroad, where with the frequent example of poor governance, they cast aspersions on everything. This establishment is utter confusion, chaos from which one can only think of the Tres Bolas pawnshop. There the small objects become thinner than smoke and the large ones take on a uniform aspect, the spherical form… It would be much better if by all means possible you tried to place all your collections in the National Museum of Buenos Aires. It is true that they do not have a local there to display them but at the least they are carefully guarded, and the austerity of the director of that establishment does not move him to make trophies of objects, nor to puff himself up, nor to stamp correspondence with grand, fuzzy phrases or those tendentiously inspired by the aim of asking for large sums from the Public Powers, nor to mount pieces in costly, enormous frames that only serve to be thrown in the garbage, destined to be contemplated by those senators and deputies that don’t understand the things, at last opening their mouths and agreeing later to the items that he wants. There, there is no danger that a Calchaqui object will appear tomorrow in a Fueguian collection. There, there aren’t Tobas skeletons with Fueguian ribs, nor Fueguian skeletons with Toba heads. There they don’t have Chinese insects in boxes with Argentine insects. There they don’t have Algerian sickle knives taken for ancient Chinese knives nor fake Peruvian vases, nor Calchaqui bells melted in Buenos Aires, nor Polynesian weapons that pass for Latin American, nor human fossils that date from yesterday, nor fossilized skeletons mounted with pieces from different genera, nor do they confuse elephant bones with those of a horse, nor do they measure fossils by cubic meters, nor do they count the skulls in thousands, nor do they have Basques that pass for Indians. There, there aren’t Peruvian fetuses that are already formed with those that attempt to demonstrate that the Peruvian deformations (the Aymara) are natural nor Mylodon fetuses found in the belly of the mother and with the molars’ cuspids already strongly attacked by mastication, like so...but enough because I won’t ever be able to conclude. It is certain that the National Museum will never fall into the hands of a vulgar Charlatan.”

The collections, in this way, far from responding to a scientific or state plan appeared to be the result of caprice, and, above all, of a disorder produced by the lack of governmental support and of a body of employees destined to lay out the institution’s path.

Zeballos caricatured in the Argentinian satirical newspaper El Mosquito (1883).

Estanislao Zeballos, represented as an explorer on the cover of his Voyage to the country of the Araucans (1881)

*The list also included: “A large piece of painted wood found in a cave on the Argentine Lake Patagonia. -Two Cervus chilensis hunted on the banks of the Limay River, near Nahuel Huapi. -An entire skin of this animal and a skull with horns hunted close to the Andes mountains to the east of the Argentine Lake. -One Felis Concolor (puma), embalmed. -One Canis jubatus (Aguará) adult and one [young], embalmed. –One lutra from Patagonia, embalmed. One male Condor eagle embalmed. -Ten skulls and part of a skeleton of several whales from the coast of Patagonia. Sixty skulls of cetaceans from the Argentine Republic.-Twenty skulls of Rhea Darwinii.-A collection of animals in spirits, of more than five hundred different ones. A collection of foreign mollusks. A collection of actual Patagonian mollusks. A collection of crustaceans, and zoophytes (Patagonian and foreign ones. Five skulls of otary, or seals. Two legs of a Dinornis from New Zealand. One skull, one femur bone, one tibia, one pelvis, one sacro, two tusks, several vertebrae, and bones of the front paws of the Panochtus tuberculatus. A skull of the Glytopodon Asper. -A part of the jaws of a young glyptodon. -Loose bones of animals such as the Mylodon, Glyptodon, Toxodon, Sceclidotherium, &c. Fossil remains of Tertiary mammal[s] from Patagonia Tertiar. Part of the skeleton and of the shell of the Eutatus Sequini. Part of the skeleton of an immense Quaternary tortoise. Fossil bones of deer, viscacha, etc. A collection of foreign mollusks. A collection of fossil argentine mollusks. A collection of fossil zoophytes. Five boxes of foreign insects. A skeleton of a Cervus tarandus (Reindeer) sent by Mr. E. van Volxen, from Brussels. A collection of Argentine minerals. A collection of pieces for study. A collection of rocks from the interior of the Republic, and from the Patagoian territories. - “Writing of the donation of F. Moreno” González, Joaquín V, and George Wilson-Rae. The National University of La Plata: Report Relative to Its Foundation. Buenos Aires: Graphics Works of the National Penitenciary, 1906. Print.

In the whirl of these contentions, also in 1889, Estanislao Zeballos (1854-1923), politician, novelist and promoter of scientific studies in Argentina, would donate his own museum to de La Plata: this was made up of his collection of skulls and antiquities gathered on his voyage to the land of the Araucanos at the end of the previous decade. Indeed, in 1879 Zeballos collected diverse material relics from the Indians: the seal and documentation from the Chiefdom of Callvucurá and the remains of the bodies of the Indians killed there shortly before. In his words, he visited the battleground guided by an Indian guide:

“La Rosa Herrera had proposed to show me the battlefield which I have made reference to and give me some of the objects that were found there, for the museum that everyone had already declared themselves collectors of…As we got closer I read in the traces on the ground the sinister scene which had taken place there just six months earlier…dead horses, with their skin nearly intact still, broken spears, saddles, ponchos and Indian corpses, all appeared here and there in scattered disorder…The corpses of the Indians were still decomposing and the majority still had flesh on the bones and some had their heads conserved fresh, with hair, and the facial features nearly intact…The Correntino Salazar took part in this combat, and he brought down the Cacique General, commandant of the Indians in the action. He remembered that the Indian had fallen close to the banks of the river…and with such fortune that it was impossible not to seek out, as it interested me greatly, what had happened to the skull. We found it, finally, and the identity of the corpse was established quickly by the soldiers…I took the skull with six lumbar vertebrae. It is a skull of the true Araucan type, with its grotesque form, without symmetry, depressed or outstanding, and its remarkable volume. The skull retained even the skin, three millimeters thick in the parietal and frontal lobes to the nostril with its hair between grey and black. The putrefaction had respected this part, which stayed in contact with the saline, and, washing it with alcohol and spraying it with phenolic acid, I was able to conserve it during the entire journey in order to offer it to scholarly assessment, as a valuable memory of my pilgrimages to the desert of the fatherland, which I longed to understand, and also as the skull of the final cacique killed heroically in defense of his guard in the most remote refuge: in the uninhabitable wilderness.” (Zeballos, 1960: 282-3)

One of the most relevant features of this collection—more than the infallibility of classifying a skull on simple viewing—consists in the proper names with which —where the individual was channeled into a series—the remains were given a name and happened to belong to a concrete historical character.

Neither Zeballos’s word nor authority was questioned, and the authenticity of this nomination was never placed in doubt: why agree to having it be handled by them? These materialist souls knew well that the Museo de la Plata was not only a junk shop, a pawnshop of boleadoras, but also that the relics of the saints were mounted with animal bones or from individuals with hardly noble intentions. In this case, the description of the recognition of the body of Gerenal turns on the criteria used to determine the identity of the corpses. Zeballos did not need witnesses, nor instruments nor measurements, to certify his findings. The name Gerenal evoked this “predatory figure”, embodied in the literature and in the pictorial descriptions of malones.* The possession of “his” skull, or put better, the skull attributed to Gerenal, would later be well complemented by the use of the names of the caciques and their “dynasties” to title other books by Zeballos: “Callvucura”, “Paine”, and “Relmu” (chronicles of their defeat) but also Zeballos’ path through literature, the law and politics. The skulls baptized by Zeballos would be passed on to the Museo de La Plata, adding to those of the Indians who died there, and the hundreds of skulls accumulated since the 1870s. The Museo de La Plata, with uncatalogued collections, subject to change in its permanent objectives as its only means of survival, would arrive in the 20th century with complete sections unstudied and without having been inventoried. The series —mired in disorder— served, nonetheless, to open politicians’ mouths.

*Malónes, as they are known, were the fast and sudden attacks by mounted indigenous forces against enemy columns or Creole populations, fortifications, or establishments, with the objective of the acquisition of cattle, provisions and/or prisoners. The canonical image of these attacks appears in the work of the Bavarian Mauricio Rugendas (1845), in La Vuelta del Malón (The Turn of the Malón) (1892) by the Argentinian Ángel Della Valle and in “Malón Por Un Electrodoméstico” (Malón for a Home Appliance) by Fernando “Coco” Bedoya, 1996, presented recently in Lima in his show “Perder Los Estribos” (Fly Off the Handle) (Sala Luis Miró Quesada Garland de la Municipalidad de Miraflores, May 2018)

Anthropological collections in the era of Francisco Moreno, that speak – approximately – to the years in Ameghino’s description

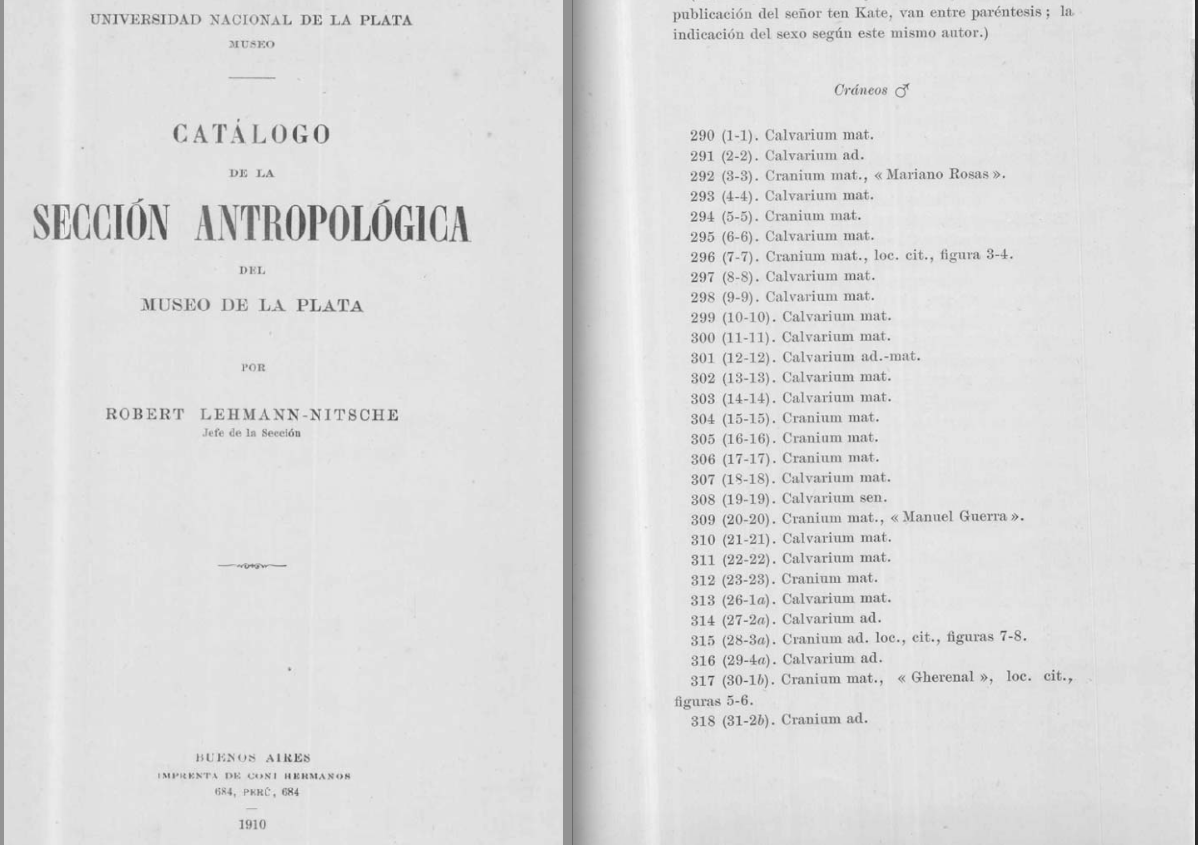

In 1897, the German anthropologist Robert Lehmann-Nitsche (1872-1938) would arrive at La Plata to take charge of its anthropological section; in 1911, he would publish its catalog. For the historian, the catalog exhibits a character contingent on the formation of the collections; there are, for example, the admissions from the so-called Museo Bennati-Sampayo, the traveling museum of an Italian charlatan that toured the Southern Cone between 1870 and 1886 (Podgorny 2008). Not only that: in the case of the Araucan skulls, they were identified according to the Zeballos’ literary work (p. 31). In spite of the fact that Lehmann-Nitsche put the proper names in quotation marks, he does not doubt them. The 1911 catalog consolidates, in this way, an order that is not so: some osteological conjunctions that result from the lack of order, from haste, from the political urgency of giving meaning to the accumulation of objects in a space questioned on various occasions by the governor, by its scientific rivals, by the press. That order includes the identities granted to the skulls at distinct moments of their history, but never proven, a relevant fact as they are tested today, as in the case of the collections of the University of Turin’s Museo Lombroso.

In 1927, the same Lehmann-Nitsche, on writing up his guide for visiting the anthropological hall of the Museo de La Plata would describe the vitrine where they exhibited the skulls as a kind of pantheon to the “heroes of the desert”, to those defenders of the fatherland’s ground from the foreign invasion. With that, this “German scientist with a Creole strain” not only affirmed identities but brought the skulls into the warrior cult emerging from the earth, where the gaucho and the Indian were the brave spirit of the Pampas incarnate.

Catalog of the Anthropological Collections of the Museo de La Plata

The hall’s reform over the next decade would abolish this arrangement and the heroic skulls would pass into use in physical anthropology courses whereby to practice the use of the compass and other anthropometric instruments. There have to date been no historical studies that have tracked down how it came to be accepted that those remains pertained to the identities that were assigned them in the catalogs, made much later and in the contexts mentioned above. On the contrary, without knowledge of these histories, the Museo de La Plata is conceived of and, likewise, questioned as a project in the same way that its founder planned—things that, in reality, were never settled. It would seem that revisionism likes to believe that the past enjoyed more stability than the present.

At the same time, contemporary claims assume, as at the beginning of the 20th century, the authority of the catalog. At the same time, that historiographic version of the role of Francisco Moreno was coined by him and ratified by the nationalists on the right in the 1940s, when Moreno, a scientific personality little respected by his contemporaries, congealed as an archetype of Argentinianness, sentinel of Patagonia and of the sovereignty of Argentina in the country’s south.

Museo de la Plata in the Era of Repatriation and Reburial

In 1989, 100 years after Zeballos’ donation, the World Archaeological Congress, based in Southampton, convened a meeting in Vermillion, South Dakota. (WAC First Inter-Congress: Archaeological Ethics and the Treatment of the Dead; Vermillion, South Dakota, August 7-11, 1989) It focused on the indigenous claims, primarily in Australia and the United States, to withdraw the exhibition of bones, skulls and funerary objects of their ancestral cultures. They defined their exhibition as a profanation of the objects’ sacred character.

Coincidentally, there was a movement that took shape in Argentina, originating in other latitudes and in local claims, that raised questions about the same things, though based on other arguments. In this section, I would like to show the distinct characteristics of these claims —in a contingent manner— in order to articulate the creation of an argument around links of belonging between the skulls and the living. Far from emerging from the communities themselves, this discourse was constituted in the interaction of distinct actors, who were steeped in the French culture of memory (pantheons, cemeteries, memorial plaques, monuments, history museums) and who inherited, in the context of the restoration of democracy and the decade of the 1980s, laws about indigenous rights and the clearing up of the location of the disappeared during the military dictatorship.

Philippe Boiry (in suit and tie) and Lorenzo Cejas, Pincén, Barón de Carhué (to his side in the lower photo), Photocopy of the documents held by Lorenzo Cejas (Personal archive of Irina Podgorny)

The Mapuche Pantheon

“I came here neither to demand nor to sell anything” – asserted Philippe Boiry (1951-2014), a French journalist who carried the title of Prince of Araucania, in 1989, while visiting Argentina. “I am here to lay the cornerstone of the Mapuche Pantheon in Treque Lauquen. On Sunday I will participate in an act of protest that will take place in front of the Museum of Natural Sciences of La Plata, a place where skulls of many Pampa and Mapuche caciques are to be found, which, in their time, were trophies of war and that now must be returned to be placed in the Mapuche Pantheon in Trenque Lauquen…I am not here to claim territorial or political rights, even if I am defending the authenticity of the kingdom founded in 1860. I am concerned with the situation of the Araucans who suffer discrimination, injustice and who live in misery, and I believe that we should preserve their culture because the aboriginal problem is growing. Nonetheless, it will not be solved by redoing history, but by correcting the errors.”

His arrival coincided with the end of the government of Raúl Alfonsin and the trials of the military junta. The first lustrum of the return to democracy was finished — the context in which the national senator Fernando de la Rúa (future ex-president after his lamentable exit in 2001), in 1985 presented the “Law of Protection and Support for the Aboriginals and Indigenous Communities.” Even before the law had been approved by the Chamber of Deputies, the Comunidad Indígena Cacique Pincén from Trenque Lauquen, a city to the west of the province, initiated the procedures before the government of Buenos Aires to grant them public land, and city property, in lacking states of hygiene and conservation to, once refurbished, install an Indigenous Museum and temporary housing for people, poets, historians and “all those who want to understand the mode of life of the natural residents of that immense Pampas.” In internal documents on the other hand, the demands were broader: as direct descendants of Chief Pincén they demanded all the lands spanning from the Atlantic to the Andes below the fortified line, declaring to never have accepted the illegal seizure of those lands, since 1810, by the Republic of Argentina. Close to Lehmann-Nitsche’s conception, they did not question the colonial order, and, curiously, in the actions organized by the community, they sang the national anthem, used the national flag, and invoked the heroes of independence (Belgrano, San Martin). That same year, the municipality granted a pension to the elderly “grandmother Marcelina Pincén de Cejas, an authentic historical relic of the Trenquelauquenches.”

Sketch for the Mapuche Pantheon in the Cemetery of Trenque Lauquen.

Beginning in 1988, Lorenzo Cejas, the great grandson of Chief Pincén, and the leader of the community bearing the same name, “Baron of Carhué” in the sphere of the new prince of Araucania, promoted the erection of the Mapuche Pantheon for which the municipality wavered between two conflicting designs: a pyramid and a niched column. It was then, upon the prince’s visit, while Pincén was arrogating the idea of the pantheon with the support of various senators, deputies and provincial politicians, that Troy burned - at least in Trenque Lauquen among the specific indigenous leaders who looked on with distrust as they were overshadowed by Philippe Boiry.

The Trenque Lauquen newspapers took out an editorial where they ruminated that the supposed prince was coming to usurp the “old project”, which had originated during the last negotiation of the municipality’s mayor Juan Jaime Ciglia (1973-1976, government of Juan D. and Isabel Perón) and his ordinance number 78 of 1974. For this, the commune had ceded a parcel located in the extreme northwest of the cemetery so that they could construct the Mapuche Pantheon there, in the years during which the most nationalist right dominated the country’s approaches to culture and education.

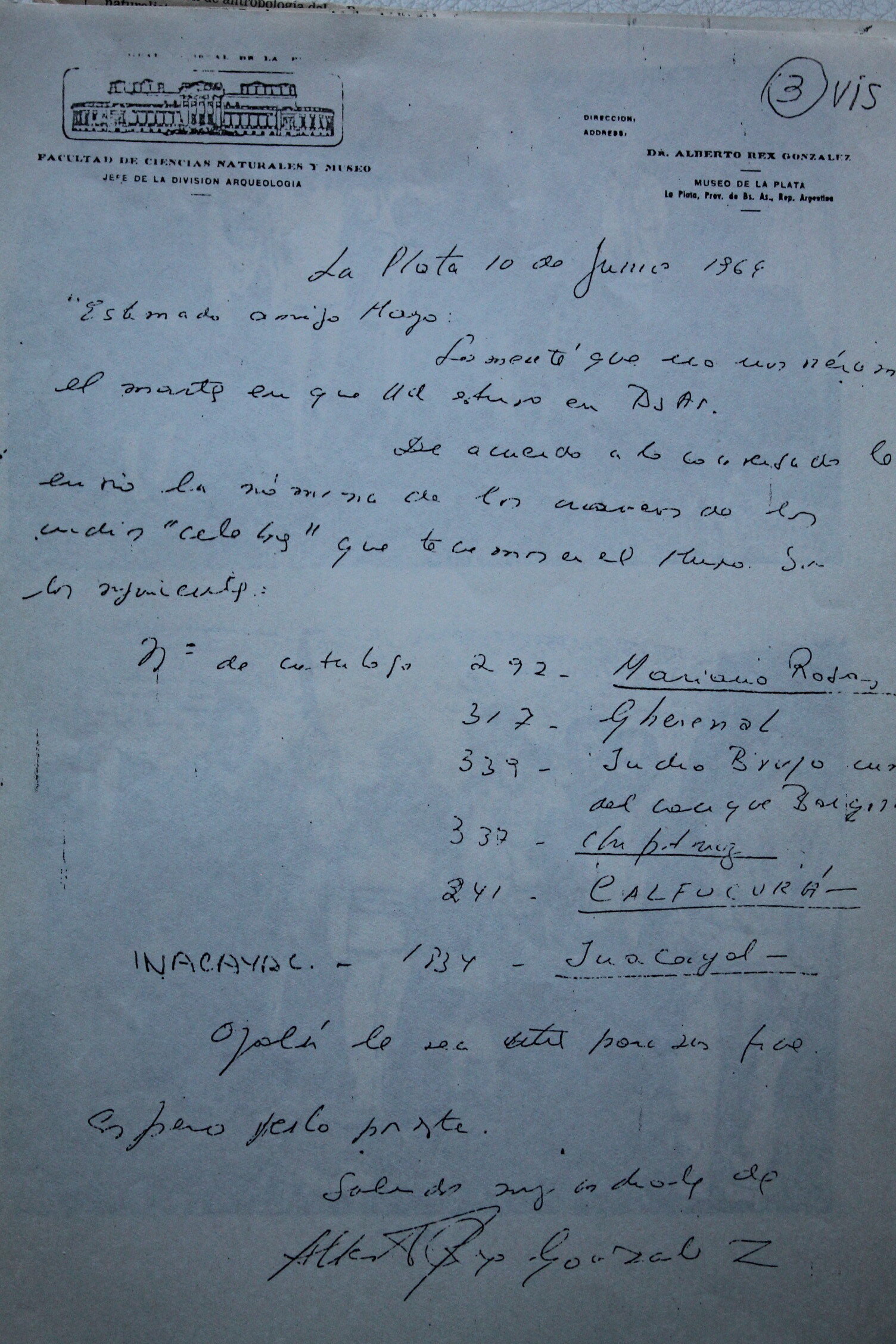

The project in reality belonged to the local historian José F. Mayo, pharmacist, aviator, and vocational archaeologist of Trenque Lauquen. He, in 1964 (a dubious date, probably more like 1974) visited his colleague Alberto Rex González (1918-2012), head of the Division of Archaeology of the Museo de La Plata, with whom he had collaborated on various projects. Mayo, author of various papers about the “men from the Pampas,” had, in that encounter, come across the cacique’s skull on the worktable of the Division. Upon his return, Rex González sent Mayo the inventory of the skulls of the “famous” Indians that existed in the museum, underlining some and citing their number according to the 1911 catalog:

Copy of the Letter from Alberto Rex González to José Francisco Mayo. Photocopy of the documents held by José F. Mayo (Personal archive of Irina Podgorny)

Catalog number

292 Mariano Rosas

317 Gherenal

339 Indio Brujo, brother in law of the Cacique Baigorria

337 Chipitruz

241 CALFUCURA

INACAYAL. – 1834- Inacayal

González lamented not being present for Mayo’s visit to the city and signed off hoping that the list might be useful for his ends. Mayo, with this information, would begin to whip up the idea for a Mapuche Pantheon being granted a parcel of land in the cemetery.

At the height of the military dictatorship, in May of 1978, one year before the centenary of the so-called Desert Campaign (the extension of the southern frontier to the south of the Rio Negro and up to Patagonia), widely celebrated in Argentina, José F. Mayo was meeting with the heads of the divisions of Anthropology and of Archaeology, Horacio Calandra, and Bernardo Dougherty (1941-1997). He ratified the meeting’s objectives in a letter that highlighted that the City of Trenque Lauquen was “sensitive to the indigenous, wants to highlight in a relevant form its linkage with the Argentine indigenous past and for this has conceived of the idea of erecting a Mapuche PANTHEON in the perimeter of the local cemetery area.” The architectural style of the pantheon would be created based on the design of the Pampas textiles and inaugurated in April 1979, during the celebration of the anniversary of the founding of Trenque Lauquen. This had occurred on April 12, 1876 thanks to the initiative of the General of Artillery and Cavalry, Conrado Villegas (1841-1884), future expeditionary of the desert. The new city, in effect, was one of the centers of operations of the Northern Division of the Border Command in the advance initiated that same year.

The letter from this “town apothecary” was dedicated, then, to clarifying what he understood as the “Mapuche” and which caciques needed to be included on the inventory of those placed in the pantheon. This was based on Esteban Erize and his annotated Mapuche-Spanish dictionary. In this, the Mapuches occupied a vast zone that included the south of the current provinces of Mendoza, San Luis, Córdoba, Santa Fe, the totality of Buenos Aires, La Pampa, Rio Negro and Neuquén, and the north of Chubut, a setting that coincided with the Desert Campaign. “We have for Mapuches those caciques whose tribes covered the territory noted.” In the museum they had identified the remains of Mariano Rosas, Gherenal, Indio Brujo (relative of Baigorria), Chipitruz, Inacayal and Callfucurá, “this last one the Great Man of the Pampas, something akin to a San Martin Mapuche who was treated—and here he paraphrased Zeballos—as a peer by Rosas and Urquiza, who gave gave him the ‘royal’ seal.” They requested, likewise, “the list of other Caciques and Capitanejos whose remains were identified as being held in that museum and that could be entered into the custody of the city, under the conditions that the museum establishes and with the measures taken to secure their perfect conservation, as has already been discussed. If the inventory should be quite extensive, it can be selected based on the principles of their action before the [arrival of the] expeditionary army or their adhesion to the “huinca” breakup.” He pleaded for the list to appear of the Chiefs whose remains could possibly be ceded to incorporate them into the official request. It would have been enough to go to the Museum library to read the 1911 catalog: there, for good or bad, they were all listed.

The transaction didn’t come to fruition. Mayo returned to try it again in 1986, this time with the intermediation of the Trenque Lauquen-born museologist, Roberto Crowder (1942-2009), by then employed in the Municipality of La Plata. Earlier, in 1984, the Deliberating Council of Trenque Lauquen had arranged for the free use in perpetuity of a piece of land in the local necropolis where they buried the remains of Paula Rinkel. They declared it a public monument and mandated the construction of a memorial mausoleum, with the municipality in charge of its preservation. Crowder, in 1986, had already met on two occasions with the dean of the faculty and museum. But now he promised a happy ending: “It is in the spirit of the current museum administration a preoccupation of giving back the cultural baggage accumulated over so many years in order to stimulate the development of the distinct regions of the country.” Crowder maintained: the dean had taken it as a promised act that would not only do justice to a part of “our Pampas’ population, but that it would give the community a great impulse and to the current task of the Museo de La Plata.” More than that, he invented an argument, a methodology that sometimes “might not be the most orthodox, but I made it with the emphasis not only on the right of these remains to belong to that region but to a more sensible part, in which the individual asks for the remains of their blood relatives to honor them and venerate them. It is for this that I ask you that you send me the list of the names and last names of the current descendants of the caciques, which in case of necessity I will use to, in their name, request formally of the museum for that which belongs only to them…” (underlined in the original, name and author of the underline unknown) For the first time in this story, the strategy turned to resorting to the “descendants” as though the demand were coming from them, possibly paraphrasing the actions of the humans rights organizations and those of the relatives of the disappeared during the military dictatorship.

Mr. Pilia, Director of Museums, Monuments and Historic Sites of the Province of Buenos Aires, now in the hands of the Justicialist (Peronist) Party, offered to “fight the financing of the work with all its might, claiming the aboriginal race as one of the pillars of our political platform.” He requested a copy of the projects in order to evaluate “what could be fit more to the historical, geographical, and customary realities of the Mapuche race.” The municipality considered the construction of the pantheon was “NECESSARY AND VITAL.” Necessary “for the justice that encloses these remains in a site for respectful memorialization” in this case, in a pantheon, from the Greek, “a funerary monument designated for the burial of various people.” The remains of these Mapuche Indians would find peace there in the churchyard and, moreover, in being in the cemetery located close to Route 33’s entrance to the city, those who would visit Trenque Lauquen would see, “to the left the Virgin of the Desert, to the right, the Mapuche Pantheon […] Few towns can display the glory of our own: to have the remains of the founder and his wife, the house where he lived, and that was the military commander and, moreover, the Pantheon where the remains of those great men of the pampas rest.” Vital, because it would mark an example of UNION and respect for the race that loved its earth and died for it, and, although it wasn’t said, now needed to settle for one parcel in a cemetery.

By 1988, with the skulls still at La Plata, the architect of Trenque Lauquen Zita Rodriguez de Louge, with Mayo’s advice, sent a descriptive statement of the future pantheon based on the following considerations: first, whereas the Mapuche community had not left any architectural ruins, they possessed abundant artistic elements in their ponchos, weavings, embroidery and ceramics. Second, the number of “funerary urns” would be just a few given that only five caciques had been identified (Mariano Rozas, General (sic), Chipitruz, Calfucurá, Inacayal). They reserved one for Pincén in case his remains showed up, and so the drawing included six niches and, if in the future more people emerged, it could be augmented for up to ten. They contemplated incorporating Maria Roca, apostle of the Mapuche religion; Paula Rinkel, who was the partner of Pincen; and Nauhuel Pan, the “Trompa Indian”, all buried in the cemetery. The column could be replicated in modules of ten niches, as in the plastic works of the Mapuche, reproducing the decorative “patterns” of that culture. If the funds permitted it, the sides would be coated in a ceramic of the Venetian sort, “in the end to make the image of a Pampas poncho that, falling from above would cover the remains of those who wore them while alive. The front of each cube-niche would have a marble plaque, or something similar, printed with the name of the person resting in its interior.”

note from the newspaper La Nación (L), from 2001, where the erected monument (R), is pictured. the concept, incorporating niches, is likewise present in the Trenque Lauquen pantheon project.

The second proposal further characterized by the patrimonialist discourse of the era, had a systemic conceptualization articulated by three elements: the truncated pyramid that symbolized the power and the political organization of the Mapuche culture generated from the figure of the cacique, with its sides oriented to the fourth cardinal directions, each one with a door. Within the pyramid, a cylindrical structure existed for the niches with the remains of the caciques, the symbolic place of veneration and dissemination of the Mapuche culture. One wall served as a visual aid:

“producing a virtual visual closure above the West door, negating it. It has an opening above the line of sight of the South Door which symbolizes a window into the Mapuche civilization, that developed in the South of our country. The basement constitutes the element above that which settles all the symbols and represents the earth, the sole source of the riches of the Mapuche and the reasons for their persisting claims. Above this, a crack has been traced formed by two lines. The straight symbolizes white culture and progress […] the curvilinear, the existing Mapuche civilization.”

Ceremony in LeuBucó (“Restitución” by Mariano Rosas, 2001). Photo, the author

The Mapuche Pantheon was not realized. The pyramid, instead, reappeared 15 years later, for the funerary monument to Mariano Rosas, in the province of La Pampa. In 2001, they erected a tomb with a basement of 2x2 meter logs (multiplied by 4, a significant number in Ranquel cosmogony. It was made by hand in caldén wood (Prosopis caldenia), representing the four most important dynasties of the ancient Ranquel Nation: the lines of Carripilum (to the north), Duck Feather (to the west), the Foxes (to the east) and the Tigers (to the south). On the side corresponding to the Foxes, to which Mariano Rosas belonged, is the entrance where his remains were introduced to Leubuco earth. The pyramidal form – quite Patagonian – signifies the trip from the “umbilicus of the earth to the light.”

Almost all the protagonists of this story have died. As testimony, these photocopies are left; I ignore whether the municipal archive still exists. The skulls seen by Mayo in Rex Gonzalez’s laboratory (which after the 1940s were retired from exhibition), were dispersed among distinct communities with distinct destinies; one monumental, the other the mere earth. The decade of the 1990s would see the US American and Australian demands for the taking down of exhibitions of objects claimed as sacred from their museums and fights for the repatriation of the distribution throughout the world. The role of the international indigenous organizations and the World Archaeological Congress (WAC), which, since its beginnings in 1986, had incorporated indigenous representatives into its forums was not minor. In 1989, few archeologists and anthropologists from the Museo de La Plata knew of the existence of these skulls or the demands in progress. The situation now could not be more different: in the first decade of the new millennium, it was confused with the new turn in discourse toward that of the disappeared during the military dictatorship. Today, no one, or almost no one, remembers that these demands initiated in the 1970s nor do they contemplate the origin of many of the words and ideas repeated without thought being given to their source. Nonetheless, as one can see in the pyramid, the past adheres to each object. Overlapping, surviving, scrambled with the residue of the most contradictory projects, where the disappeared, for example, coexist with the ideas from the protestant world; where the temples lack images and filigrees they ignore not only the form of the saints’ relics but that of the corpse that presides over the ceremonies of the Roman Catholic Church.

Teachers, flag bearers and community members in front of the Pyramid for Mariano Rosas (2001) (Photo, the author)

Restitution of Mariano Rosas (2001) (Photo, the author)

Author’s note: This work was presented at the EHESS of Paris in the seminar “L’Humanité exposée” in December 2018. I am grateful for the comments of Pietro Corsi, Rafael Mandresi, Elodie Richard, Jorge Villacorta, Alfredo Bernal, Andrés Hare, Susana García, Silvia Ametrano and Fernando Bedoya. Additionally, it is worth clarifying that the second part of this work is based on materials collected and photocopied in 1989 in the city of Trenque Lauqen, in the process of research carried out in the wake of the repatriations to the Comunidad Cacique Pincén. At that time, I visited the archives of the local press, the municipality and interviewed José Mayo and Lorenzo Cejas, with whom I had been acquainted in a meeting in Buenos Aires. The documents on the return of Mariano Rosas come from the burial of his remains in 2001 in Leuvucó, in the province of La Pampa, which I was able to help with at the invitation of Silvia Ametrano, then director of the Museo de La Plata and to which we arrived in the Tango 03, the presidential aircraft made available for the occasion.

Translated from Spanish by Judah Rubin

References

A. Primary Sources and Archives Consulted

“Un Juicio de Ameghino. Arqueología y Antropología”, Fígaro, June 28, 1889 (Archivo Furt, Estancia Los Talas)

“Dtor. Del Museo eleva listas de objetos que integran colección donada”, 1877, 19 Exp. 1015/1”, AHBA (Archivo Histórico de la Provincia de Buenos Aires)

“Escritura de donación de Francisco P. Moreno a la P. de Buenos Aires para la formación de un Museo Antropológico y Arqueológico, 8 de noviembre, 1877. Dtor Del Museo eleva listas de ojetos que integran colección donada”, 1877, 19, Exp. 1015/1, AHPBA.

A.I. Materials from Private and Periodical Archives in Trenque Lauquen

“Excelentísima Señora Vice-Gobernadora de la Provincia de Buenos Aires, Arquitecta Elva Roulet, carta de Lorenzo Cejas Pincén, Trenque Lauquen, 7 de septiembre de 1985” Diario Popular, Saturday, April 1, 1989, p. 10.

“Evocación en Trenque Lauquen”, La Opinión, April 23, 1985.

“Se Creará la Comisión de Asuntos indígenas. Luego de cien años de paz”. Resolución No. 14/85; July 24, 1985. Consejo deliberante de Trenque Lauquen.

“Alberto Rex González a José Mayo”, La Plata, June 10 1964. (Date questionable, likely sent in 1974)

Request for the reservation of a portion of land in the outside lot of the Cementerio Local for Construcción Panteón Mapuche – Date of initiation, December 4, 1973.

“José Mayo al Jefe de Antropología del Museo de La Plata”, Trenque Lauquen, May 17, 1978, EXP. 3437.

“Ordenanza No. 161/84”, Trenque Lauquen, December 14, 1984.

“Roberto Jorge Crowder a Pepe Mayo”, La Plata, March 1986.

Report of María de Guerrero, Director of Culture and Education of the Mayor of the Municipality of Trenque Lauquen, February 3rd, 1988.

“Memoria descriptiva: tema Panteón Mapuche”, Trenque Lauquen February 4th, 1988. EXP. 4115-59/88.

Draft of Mapuche Pantheon of Architect José Lucio Morallim department of Urban Planning of Trenque Lauquen, January 6th, 1988, EXP 4115, 59/88.

A.2. Materials from the Province of La Pampa

Mariano Rosas. Document edited for the Subsecretary of Culture, Ministry of Culture and Education – Governor La Pampa, 2001.

B. Bibliography

Erize, Esteban. Diccionario Comentado Mapuche-Español: Araucano, pehuenche, pampa, picunche, rancülche, huilliche. Yepun. 1960.

Farro, Máximo. La Formación del Museo De La Plata. Coleccionistas, Comerciantes, Estudiosos y Naturalistas Viajeros a Fines Del Siglo XIX. Rosario: Prohistoria. Argentina, 2009.

Malosetti Costa, Laura “Comentario Sobre La Vuelta del Malón”. Available at: https://bit.ly/2BezyNq

Lehmann-Nitsche, Robert. Catálogo de la Sección Antropológica del Museo de La Plata, Buenos Aires. 1911.

Podgorny, Irina. “Historia, Minorías y Control Del Pasado”, in: Boletín del Centro de la Provincia de Buenos Aires, 2, pages 154-159. 1991.

Podgorny, Irina. “Una Exhibición Cientifica de la Pampa (Apuntes Para la Historia de la Formación de las Colecciones del Museo de La Plata) in Idéias, vol. 5, no, pages 173-216. 1998.

Podgorny, Irina. El Argentino Despertar de las Faunas y de las Gentes Prehistóricas. Coleccionistas, Museos, Estudiosos y Universidad en la Argentina 1875-1913. Buenos Aires: Libros del Rojas. 2000.

Podgorny, Irina. “’Ser Todo y No Ser Nada’: Paleontología y Trabajo de Campo en la Patagonia Argentina a Fines del Siglo XIX”, in Visacovsky, S. and Guber, R. (eds.) Historia y Estilos de Trabajo de Campo en Argentina. Buenos Aires: Antropofagia. Pages 31-77. 2002.

Podgorny, Irina. El Sendero del Tiempo y de las Causas Accidentales. Los Espacios de la Prehistoria en la Argentina, Rosario: Prohistoria. 2009.

“Momias que hablan. Ciencia, colección de cuerpos y experiencias con la vida y la muerte en la década de 1880”, in Prismas, vol. 12, no.1, pages 45-65. 2008.

Florentino Ameghino & Hermanos. Empresa Argentina de Paleontogía Ilimitada, Buenos Aires: Edhasa, 2020.

Podgorny, I. and M.M. Lopes. El Desierto en una Vitrina, Museos e Historia Natural en la Argentina del Siglo XIX. Mexico City: Limusa.

Podgorny, I. and Laura Miotti. “El Pasado como Campo de Batalla”, in Ciencia Hoy, vol. 5, pages 16-19.

Podgorny, Irina and Gustavo Politis. “¿Qué sucedió en la historia? Los Esqueletos Araucanos del Museo de la Plata y la Conquista del Desierto”, in: Arqueología Contemporánea, 3. 1991-2.

Presupuesto General de Gastos y Recursos de la Provincia de Buenos Aires. Buenos Aires: Imprenta La República. 1883.

Sarmiento, Domingo F. “El Museo Antropológico Argentino”, in Obras Completas, Discursos Populares, vol. 22. Buenos Aires: Luz del Día. Pg. 135-6.

Sarmiento, Domingo F. “El Museo de La Plata. Discurso en la Inauguración de una Parte del Museo de La Plata, 20 de Julio de 1885”. Obras Completas Discursos Populares, vol. 22. Buenos Aires: Luz del Día. 1951. Pg. 302.

Torres, Luis María. Guía Para Visitar el Museo de La Plata, La Plata. 1927.

Zeballos, Estanislao. Viaje al País de los Araucanos. (1881) Buenos Aires: Hachette, 1960

Callvucura y la Dinastía de los Piedra (1884). Buenos Aires: Hachette. 1953.

Painé y la Dinastía de los Zorros (1886). Buenos Aires: Hachette. 1952.

Relmu, Reinda de los Pinares (1888). Buenos Aires: Hachette. 1952.