A Terrace in Valparaiso was originally published as Terraza en Valparaíso in: Los Nuevos Sensibles (Vicente Vargas Estudio, 2015, Valparaíso, Chile).

In mid-April 2014 a major portion of the poorest neighborhoods of Valparaiso was destroyed by wildfire. It is estimated that the fire left sixteen people dead, injured more than five hundred, rendered more than fifteen-hundred homeless, and reduced a thousand hectares of vegetation to ashes.

As though it were drawn to it by the words themselves, the fatal blaze began in the area known as La Polvora (gunpowder), later reached Las Cenizas (ashes) and from there spread incrementally until it left a vast area of the city at risk, in a process lasting more than two days. This was time enough for the fire to raise and lower all sorts of expectations among the affected population, allowing for a combusted sense of suspense among those who saw the flames approach and recede, mere accomplices of the capricious and indecisive wind. The residents organized support groups, evacuation committees, solidarity actions; over the following days volunteers from various parts of the country enthusiastically brought in aid, providing meals and shelter, helping where it was needed. The stories, and tragedies, of what is now considered the worst wildfire the city has experienced in decades, confirm in many ways what was already understood: that in disasters of this sort the social fact of misery, precarity and planning failures are significantly more decisive than the natural event. In this (to twist a turn of phrase) there is something that fire can never purify, and certainly not redeem.

And Valparaiso is a city of wildfires.

Sebastian Riffo. La noche del 12 de abril. (The Night of April 12) Charcoal on paper, 2014.

“An architect who became the president of Peru said, on referring to the then new, impoverished residents of the hills surrounding the capital’s center, that it was normal for those migrating from the Andes to seek out the territory most similar to that which they were migrating from”

At this altitude my lungs fill with the damp and freezing six o’clock wind. As though in some religious painting, the sun shines across the sea’s surface between the clouds announcing the coming rain.

I don’t have access to many images. Some archival photos, press photos mostly. One which most grabs my attention, though, comes from a simple cell phone video taken by the artist Rodrigo Vergara one of the nights of the fire. It lasts only a few seconds: a night shot bordered at its bottom edge by the mountainous horizon cut into by the reddened flames; in the foreground a living room or terrace viewed from above in which some gathered people are celebrating, talking, drinking or playing something. Or maybe, as is sometimes customary, they are gathered to get a better view of the already spectacular fire. But the still is in reality far from the instrumentalized and distracting vantage of journalism and possesses something of the intimate atmosphere of Nighthawks, the Edward Hopper painting. As in the famous canvas, the harmoniously synthesized contrast and the less metaphysical than nostalgic reflection on the extreme loneliness of dawn are here virtually duplicated in the illuminated terrace filled with warmth in the midst of the dark night of the fire. Here the reddened profile on the horizon of Valparaiso’s terrace becomes just another point of chromatic intensity before which the cheerful social gathering takes place, sheltered from the fire and the night. Looming on the background’s horizon the fire is a decorative sign that does not interrupt the revelers.

As with works typified by Hopper, the image which we have here, more than capturing the particular moment in a collective drama, comes to life in a manner quite disparate from what its urban space produces: in a certain fashion, an implacably contemplative vantage of the other and the self understood as the fruits of a leisurely voyeurism that defines the social, spatial and virtual distances by which we keep ourselves safe from harm and which give shape to privilege. There is something Nero-like, perhaps, in this terrace and in the terrace from which we survey the catastrophe; the manner in which it is assumed Nero set fire to Rome and sat to contemplate the flames as he chanted the verses in which Priam sets fire to Troy. An unfounded rumor, according to some historians; that he wanted to blame the subterfuge on a new dogmatic and belligerent religious group and to unleash repression in kind, according to others. These versions have both, themselves, been reproduced and altered. What is certain is that of Rome’s 14 neighborhoods only four survived intact after the fire, while even less is known of the fate of the 800,000 inhabitants of the time and ignored altogether are the number of victims. Yes, the narrowness of the streets is known, the limited access to the hills and to the slums; that the density of the houses impeded all forms of aid; that the city burned for seven days. Also noted is that official cohorts and troops prevented all efforts by the inhabitants to put out the torches. Historians, instrumental actors on behalf of these and others in power, have always concentrated on the number of monuments that disappeared in this fire that, being things, are by definition as perishable as people themselves.

It is this quantitative marker of the monumental in place of the people that has defined Rome as eternal. This eternity, to the diminishment of its citizens, is one version of the mythologizing of raison d’etat identified in a spatial and monumental fashion in urban discourse. These are the perspectives which illustrate what David Harvey defines in each urban layout as a spatialized morality, or if you prefer, a specific staging of power.

book burning in argentina, 1978

But fires burn plenty of things. Despite the reconstruction in process, the remains of domestic life are strewn among the ashes. Among the remains, the unusable structures and giant empty spaces. And what was the communal library that a university professor cared for in his own house reduced to powder by the fire. I don’t know now on which of Valparaiso’s hills to be exact, but in every part where we were on foot that which had been donated to the community was the property of all, as a service to all, for the purpose of complete reconstruction.

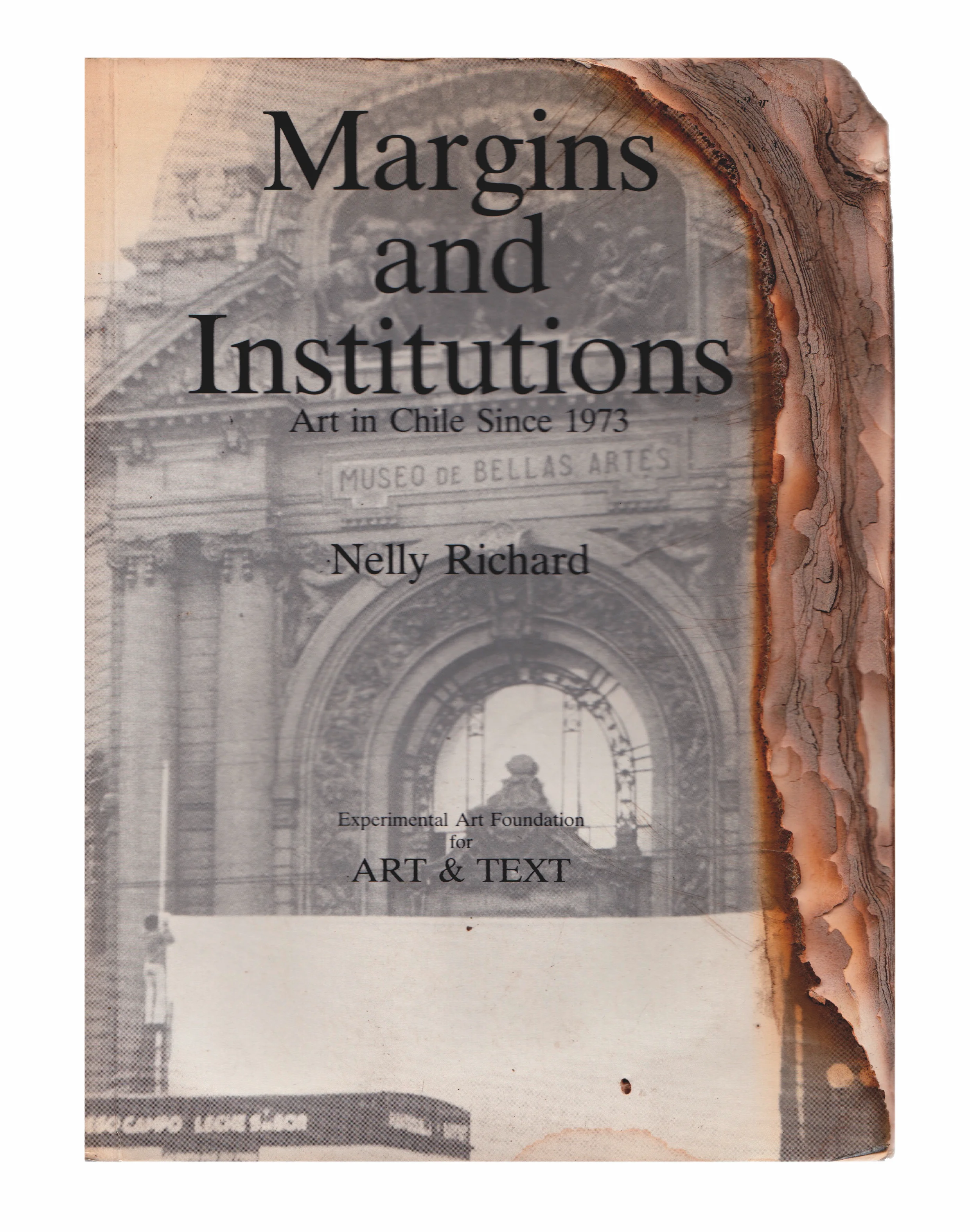

If my memory serves me, after a fire in my own home caused by a candle during a blackout in Lima, few things burn quite as well as books. And where they don’t burn entirely, water certainly doesn’t improve the results. That night a bombing that sabotaged some high-tension towers burned my books, my computer and various texts and poems on paper that perhaps deserved to be burned. The following day, from among the ashen sludge, paper pulp and water, I rescued only a half burnt Cuban edition of the complete poems of Lezama Lima, fat as its author, some of the Collected Books of Jack Spicer and an Australian edition, the first, of Margins and Institutions, by Nelly Richard. Simply seeing that half burnt copy with a photo of the front of Bellas Artes and the subtitle Art in Chile Since 1973 makes me shudder remembering that treacherous fire. All of these visions superimposed: the violent year of ANFO and dynamite, of the blackout; the fateful year of 1973; the burnt paper border with its photo of the institution in the book - all of this taken together leaves me short of breath. I open the Spicer book that now, having been burnt, begins more than 40 pages in. But one can still read: When the house falls you wonder / If there will ever be poetry / And you shiver in the timbers wondering / if there will ever be poetry / When the house falls you shiver / In the vacant lumber of your poetry.

Copy of Margins and Institutions by nelly Richard

Rodrigo Vergara

In June of that same year and after a long absence, I disembark in Valpo, on a very sunny day without much wind.

On the second day of my stay, my hosts, the artists Vicente Vargas, Jose Pablo Diaz known as Cordero, Rodrigo Vergara and I walk up La Polvora to survey the rubble and reconstruction. Valparaiso is built on 42 hills. From the highest points you can make out which areas were the most affected at a glance. What has always struck me of the poverty in the gullies and hills of Valparaiso is its similarities with other equally poverty-stricken areas; not their differences, nor the idiosyncratic ways in which all populations cope or make ends meet, but, rather, their mere familiarity. In this case it was the carbonization of the debris that further emphasized their likenesses.

The reasons that people decide to live at this altitude are almost always driven by the desire of a minority of the residents to be at a distance from the city’s center or to have a more contemplative view. For everyone else, it stems from having no other choice. An architect who became the president of Peru said, on referring to the then new, impoverished residents of the hills surrounding the capital’s center, that it was normal for those migrating from the Andes to seek out the territory most similar to that which they were migrating from. He left out, curiously, the sordid precarity of their living conditions and the complete lack of public services. For those residents of the highest parts of Valparaiso daily challenges include walking access to places that neither transportation nor help can reach and their coexistence with the natural environment, which is both treacherous and flammable.

Valparaiso, chile. June 2014

valparaiso, chile. june 2014

The vision of this power structure from this terrace at the Camogli lookout here on Cerro Yungay in Valpo at six in the evening, the hour at which the lampposts switch on at once and the schoolchildren and population ascend in slow motion.

Patrician Valparaisans who wallow in their leisure on the terrace while Rome burns: That these same people watch the sunset or the fire clutching their television remotes. That the same people make lists of the things they love or hate. With this contemplative air, Marker says in Sans Soleil about another, similar aristocracy: with this comforting melancholy. And one might also say with a certain horror.

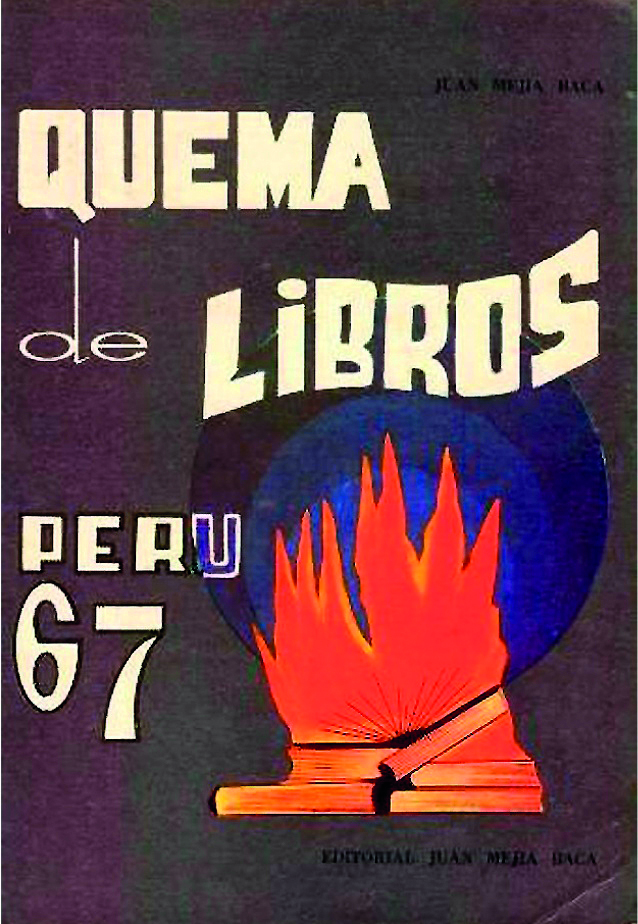

copy of Quema de Libros (Book Burning) by juan mejía blanca

From all the fires this. From all the libraries burned in broad daylight and without the romanticization of nocturnal fire. From all the pyres filled with books lifting their smoke toward the sun. From all of these burnings, from all of the lootings, from all of the dispossessions, from all of the fires. It is the month of May in the year 1933 and Goebbels coordinates and carries out the burning of books disapproved of by the regime in more than 20 German cities. This is the modern reference for an act repeated too many times since. The burnings are held before the eyes and patience of the entire world: they are a warning and a lesson. And they are a harbinger of something worse that won’t be quite as easily seen. The scene will be repeated at various times and in various places.

In September 1973 Ariel Dorfman sees, from the window of the Argentine embassy where he has sought asylum in Santiago, the military trucks that carry hundreds of thousands of confiscated copies from the Quimantú publishing house. Over a number of months, the public book burnings are reproduced at the hands of the dictatorship and are, again, a warning and a lesson and the visible portent of something worse. That day Dorfman thought of the passage of “full boxcars heading toward their Chilean Auschwitz.” Though Dorfman evidently saw no boxcars, but, rather, trucks. Still, the metaphoric reference to the death trains of the Shoah reproduces the indelible shiver of what happened thirty years earlier in Europe, and perhaps also the idea that it would be equally impossible to stop them. That day Dorfman likewise “sees” the titles of the books burning on the pyre, including his own. But in this metaphorical vision Dorfman, in reality, has divined with clairvoyance the defeat of a process already truncated for the future. Seven years later, under another dictatorship, an Argentine judge rules on the burning of a million and a half copies (the calculation is more than five tons of paper) of the Centro Editor de America Latina, CEAL, in the wastelands of Avellaneda Partido, south of Buenos Aires. Since their founding in 1966, CEAL collaborators had been incarcerated or hunted by the Triple A and so the order issued “juridically” for the incineration of books discomfiting to the regime is the material corollary to and symbolic of a lesson learned in beatings and the memory that fire, disappearance and death usually go hand in hand.

Other bonfires are prepared in neighboring countries, but it is six again in Valparaiso and raining. Below, the ring of lights around the port; schoolkids are swirling under a single umbrella, giving form to a species of battered flower.

Unlike the now familiar atrocities, which existed in the invisible kingdom of the mole, the confiscation and burning of books and archives were in general public acts of punishment. But not in Peru.

In 1967, under the government of the architect Belaunde, the Lima editor and bookseller Juan Mejia Baca denounced the existence of a secret index and government authorizations for the burning of books, and, later, for the bloody repression of the 1962 Campesino uprisings and the 1965 guerrilla rising in which the young poet Javier Heraud, among others, was killed after his capture. The burnings and executions constitute a direct attack on memory and on the futures now detached from it - above all in the systematic destruction of the affective webs it contains. A coup directed at subjectivity or, as in the Chilean case, an aesthetic coup in the institutional imposition of new visual and behavioral strictures and paradigms.

It is at that point on that day in September 1973 that Ariel Dorfman sees the historical horizon darkening and, in contrast to Hopper’s protagonists, pays attention and observes the decline of the “fruit of the country’s collective power” to bring about an emancipation that now has no place, nor will it continue to in the future imagination. But Dorfman himself, stemming from his metaphor about Auschwitz, is unable to foresee a new regional reincarnation of the industrial crematoria. Even while lacking the methodical precision and coldness of the final solution, it is calculated that in the ovens of the Los Cabitos barracks, in the city of Huamanga, Ayacucho, they cremated the corpses of hundreds of civilians from diverse backgrounds, arbitrarily accused of collaborating with Sendero Luminoso (SL). Kidnapped from their homes, savagely tortured, and later summarily executed by a bullet in the neck, they were first buried on the outskirts of the barracks, in the gorges and in so-called dumps, during the first three months of the operation. Two years later, as part of new orders for concealment, they were disinterred in order to be cremated together with their belongings. As the headquarters for anti-subversive operations after 1982, the Los Cabitos 51 barracks functioned for a number of years as the center-point of a network of 60 military bases scattered among the three departments of the emergency zone. Because of the long hell of its operations, the number of cremations carried out is still not exactly known. Only a hundred sets of remains, including children and fetuses, were found beneath the fake oven which was meant to simulate an abandoned brickworks. In contrast to the other cases cited in this text, the industrial incineration of bodies, of clothes, of documents in Los Cabitos was marked by a complete lack of visibility and suspicion, though performed practically in the urban center of Huamanga. In fact, if there is one thing that characterizes these and other monstrous bonfires in the Peruvian Andes it is the absolute lack of images and strict military secrecy in what was developed with open complicity from the judicial and governmental authorities. But in the hunt for images, one finds precisely the eight journalists and photographers who came from Lima in 1983 when they were attacked and killed with machetes and stones in the hamlet of Uchuraccay, at the hands of a group of community members who had received orders from the local military commander to repel intrusion. Here, the event could be reconstructed from the images extracted from the rolls of film found in the reporters’ broken and recovered cameras. As for the rest, however, for the events of annihilation and cremation of the detained and disappeared civilians of Ayacucho during these years, one can only say, picking up a line from Didi-Huberman concerning the status of the image in the context of the crematoria of the final solution, that this continues to be an unimaginable experience. However, unlike the Nazi extermination camps, this was perhaps “imaginable.”

valparaiso, chile. june 2014

In the conception of forms of annihilation of life and memory of the civilian population, the Peruvian variation on bonfires didn’t enact a simulacrum of public spirit nor did it produce any exemplary gestures. The SL itself performed its own raids in which it burned archives and libraries, in addition to the bloody liquidation of animals and civilians.

Between the beginning of the 80s and the middle of the 90s the confiscation and burning of books was a quotidian part of military operations. So too, as in other regional experiences, was auto-censorship. A news report from 1984, for example, cites a complaint in which students from the University of Huamanga had begun destroying books by throwing them from the Alameda in order to avoid being detained. Ten years later, something similar would happen to the same owners in the burning and burying of copies of Carpeta Negra, a portfolio produced by the art/architecture collective N.N. During this same period, a congresswoman denounced the sacking and burning of books from the library of the University of Cantuta. And in 1992, as reprisal for an attack by the Sendero Luminoso, the famous events transpired in which a professor and his students from that same university were kidnapped from their homes by state forces and later killed. Their charred remains were found on the outskirts of Lima.

From the high temperatures of the cremation a bunch of keys was salvaged, which, on being tested in the doors of a student dorm permitted the easy identification of the remains. They were put in evidence against the kidnappers, who were later amnestied, and who at present still remain unpunished. And like that, the employ of fire as a favored instrument of disappearance. Like that, the obliteration of everything. Like that, the arrogance. Like that, also, the nickname “Kerosene” for the most celebrated of the repressors of this period, a psychopath in the service of the state, who’s actual name, useless at the moment, I will omit as a stain of history.

The list goes on. And the wildfires, too. But it is necessary to finish up. I turn to walking and breathe the cold air of evening. The streets that slope downward from the hill toward the port await me. Ready to follow you or jump up around your neck with equal joy, the romantic dogs are rearranged in the corners of Valparaiso.

Translated from the Spanish by Judah Rubin

valparaiso, chile. june 2014